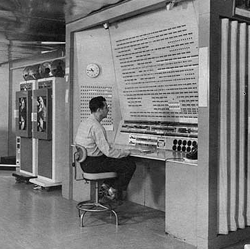

I’ve had a computer on my desk at home since 1984. A lot of them. Zenith, Gateway, IBM, Dell and, most recently, a Mac Mini. No longer. I’m selling the Mini.

I’ve had a computer on my desk at home since 1984. A lot of them. Zenith, Gateway, IBM, Dell and, most recently, a Mac Mini. No longer. I’m selling the Mini.

Oh, there are still lots of computers around the house. The MacBook Pro long ago became my main box (slab?). And there’s the iPad and the iPhone. But it felt like the end of an era.

This weekend I’ll replace my printer and scanner with a wireless all-in-one from HP and as I started making room, I was struck by how many usb hubs and power-strips were being relegated to a box in the closet.

Yesterday I had a chat with one of our IT guys about where things are headed from a business perspective. Are we getting closer to the day when a company tells a new employee they can use their own computer (any flavor they choose) and hook into the company content via the cloud.

I took a little further and suggested the device of chose would be some sort of tablet, not a laptop. Whatever shakes out, things are going to be much different for the users and the IT folks who support them.