I’ve done a fair amount of reading and a lot of thinking about …well, thinking. And consciousness. According to ChatGPT (PDF) the two are different but related.

One view that feels right to me is that thoughts think themselves. Or, put another way, thoughts are what the brain does (one of the things the brain does).

For the past couple of days I’ve been visualizing thoughts (?) as toy balloons floating into and out of awareness. (Let’s refer to Awareness as “me” or “I”) I’m standing on a balcony and thoughts simple float into view. Unbidden. Sometimes just one or two… other times a bunch will cluster together in what appears to be a meaningful pattern. (see comment below for thoughts as bubbles and refrigerator magnets)

If I ignore the balloons, they simple float up and away. But too often I reach out and grab one (or several) and hold onto them. Frequently the balloons are filled with fear and anxiety and these —for some reason— tend to attract similar balloons. Why would someone hold onto these?

There seems to be no limit to how many balloons I can hang onto at once. Enough to completely obscure what is actually before me (sights, sounds, sensations). And, as it turns out, these thoughts are mostly unnecessary. The body is, and has always been, mostly on autopilot.

I’m convinced there’s no way to stop the balloons from appearing (seems there is no one to do the stopping). Can I resist the urge to reach out and grab a balloon? Can I immediately let it go? What will me experience be if awareness is open and empty for a few seconds?

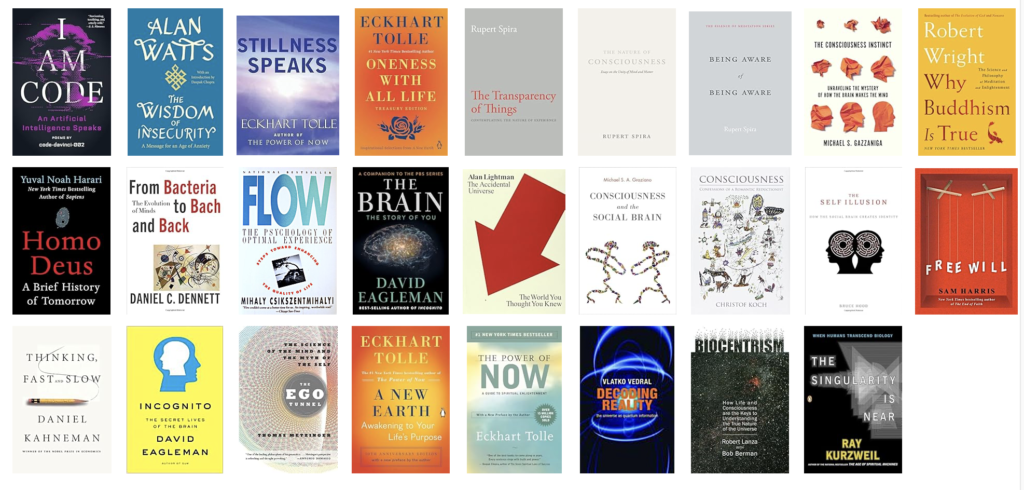

I don’t recall precisely when or how I became interested in

I don’t recall precisely when or how I became interested in