Category Archives: Media & Entertainment

Wilhelm Keitel – Nazi Field Marshal and War Criminal

Becorns

David Bird “builds little people out of acorns and sticks, then photographs them in the wild with real animals.” More on his YouTube channel.

Jeep promotional videos

YouTube: Willys, the “World’s Largest Manufacturer of Utility Vehicles,” presents the “Jeep Family of 4-Wheel Drive Vehicles and Special Equipment,” a circa 1954 black-and-white film promoting Jeeps produced for civilian use. (“One man with a Jeep can do the work of 100 men with shovels”)

Because this video runs a tad over 20 minutes, I’m guessing it ran in theaters before feature films. I recall seeing newsreels like this as a child in the 1950s. Jeeps like mine (CJ2A) were aimed at the agriculture market and this video show one handy attachment after another.

The narrator pronounces Willys: WILL us … rather than WILL eez so I’m confident that is the correct way to say it.

YouTube titles the video below: Autobiography of a Jeep and the narrator is the “voice” of a Jeep during its development and the early years of WWII. The delivery is that Pete Smith Specialty style from the 40s and early 50s (you had to be there). A little corny but some excellent Jeep footage.

YouTube description: “A small company in Pennsylvania, Bantam, invented the Jeep, but the military needed more than Bantam could produce. So they turned to Willys and Ford and had these auto titans build Jeeps. Edsel Ford joins other Ford Motor Company officials as they demonstrate their vehicles for the military.” (this video has no sound)

Okay, one more. 1940 Ford Pilot Model GP-No. 1 Pygmy

Hitler’s final memo

One more from Antony Beevor’s great history, The Fall of Berlin 1945:

“Hitler took Traudl Junge (one of his secretaries) away to another room (in the bunker), where he dictated his political and personal testaments. She sat there in nervous excitement, expecting to hear at last a profound explanation of the great sacrifice’s true purpose. But instead a stream of political clichés, delusions and recriminations poured forth. He had never wanted war. It had been forced on him by international Jewish interests. The war, ‘in spite of all setbacks,’ he claimed, will one day go down in history as the most glorious and heroic manifestation of a people’s will to live’” (emphasis mine)

Does the ‘funny’ come first?

Bad Lip Reading has an informative Wikipedia page but it doesn’t answer one of my most burning questions. The dialogue/monologue has to be funny nonsense. And it invariably is. But the words always match the lip movement. I’m inclined to believe the funny comes first but the perfect sync seems equally important.

Bad Lip Reading is the creation of Kennedy Unthank: “Kennedy Unthank studied journalism at the University of Missouri. He knew he wanted to write for a living when he won a contest for “best fantasy story” while in the 4th grade. What he didn’t know at the time, however, was that he was the only person to submit a story. Regardless, the seed was planted. Kennedy collects and plays board games in his free time, and he loves to talk about biblical apologetics and hermeneutics. He doesn’t think the ending of Lost was “that bad.”

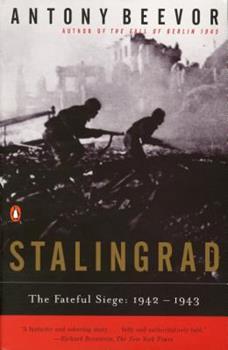

STALINGRAD The Fateful Siege: 1942-1943

I’ve only read a handful of history books (crime fiction is my passion) but they’ve all be great reads. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century; Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civ89l War Era; Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869; and Wires West: The Story of the Talking Wires. I’m currently reading STALINGRAD The Fateful Siege: 1942-1943 by Antony Beevor.

I’ve only read a handful of history books (crime fiction is my passion) but they’ve all be great reads. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century; Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civ89l War Era; Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869; and Wires West: The Story of the Talking Wires. I’m currently reading STALINGRAD The Fateful Siege: 1942-1943 by Antony Beevor.

(Wikipedia) “Stalingrad is a narrative history written by Antony Beevor of the battle fought in and around the city of Stalingrad during World War II, as well as the events leading up to it. The book starts with Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the subsequent drive into the Soviet Union. Its main focus is the Battle of Stalingrad, in particular the period from the initial German attack to Operation Uranus and the Soviet victory.” Continue reading

YouTube is the second most visited website, after Google Search

First, a bit of history: Google Video was a free video hosting service launched on January 25, 2005. It allowed video clips to be hosted on Google servers and embedded on other websites. I seem to recall putting videos online before that but they were nasty little things about the size of a matchbook and took hours to create and upload. (Google Video made it SO much easier.) YouTube launched in February 2005 and was acquired by Google in October of 2006 ($1.65 billion in stock). Google shut down Google Videos in 2009.

I uploaded my first video to YouTube in February of 2006. In the ensuing 16 years I’ve uploaded 551 videos. It never occurred to me to “monetize” my videos so I’ve never paid much attention to the analytical data YouTube sends me every month. YouTube was just an easy way to stream videos using their embed code on my blog.

Today they sent my “2022 snapshot.” In the past 12 months my channel has had 53,000 views (50,000 “watch time minutes”). Over the course of the 16 years my videos have been viewed 1,066,666 times. And I’m not even trying (to influence or monetize).

Steve Cutts: A Brief Disagreement

Beginning to Feel the Years

“But I’m going to be okay.”