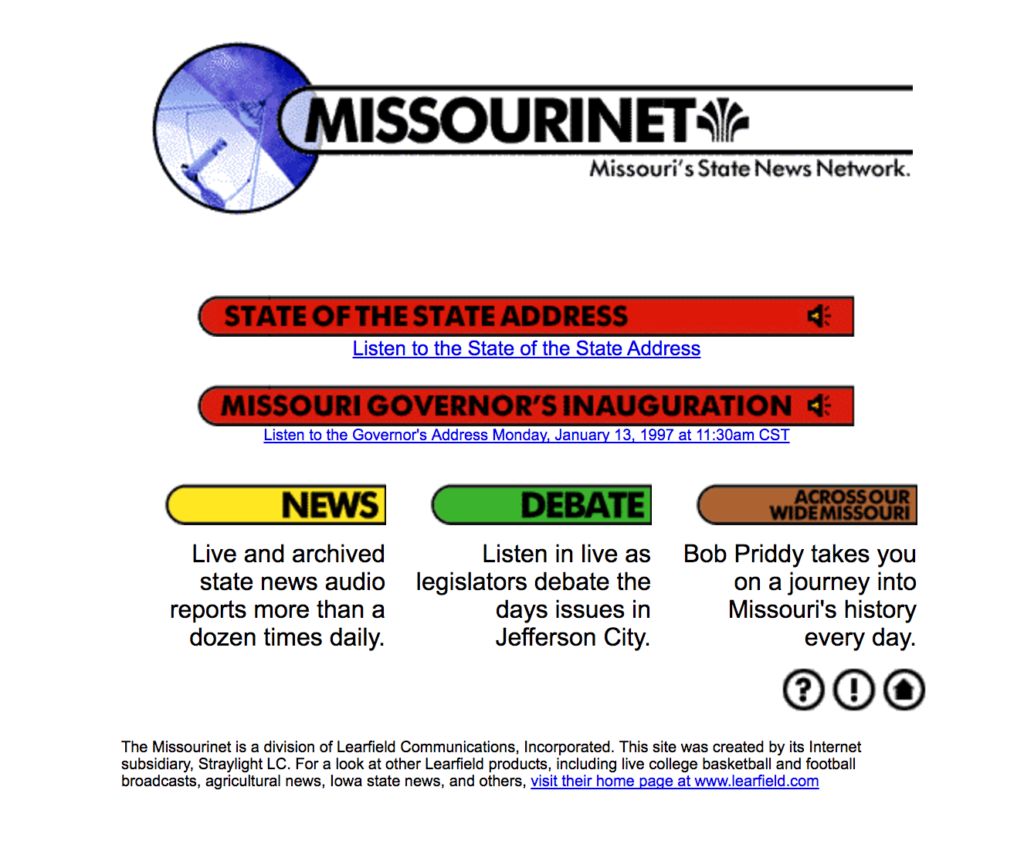

In 1996 (maybe 1997) I was involved in the first effort to stream audio of floor debate from the Missouri legislature. It was early days for streaming and the audio sounded pretty shitty. We had very limited bandwidth and the first RealAudio encoders were primitive. But it was the first time anyone could listen to live debate without being in the Capitol building (where they had audio lines to each rep’s office).

That first year I think we only streamed live but the following year we started archiving the audio as well. That, however, was nearly useless if you were trying to find a particular piece of debate in audio files that could run five or ten hours.

Not sure I can explain this but what we did was insert links to specific points in the debate (not unlike how we now create YouTube links that jump you X minutes into the video). I spent hours doing this before I dumped it on an assistant. But it allowed someone that wanted to hear debate on House Bill 123 to click a link and get pretty close. Unbelievably tedious.

We provided this service at no charge for a year or two and then started charging $500 per session. Lots of takers, mostly lobbyists and lawyers. We bumped it to $750 the next session and lost a few subscribers. It wasn’t long after that that the House and Senate Information Offices took this service over and we were out of business. It wasn’t a good “business” business but it offered a hint of what would be coming down the road in terms of streaming.

If you’ve never listened to floor debate of a state legislature, it’s hard to describe how boring this shit was. As streaming tech got better, someone would suggest they stream video and they’d take a shot at that, usually on the final day of the session. On one such attempt they had to pull the plug quickly because the cameras were showing members dozing at their desks.

Once people saw that we could actually do this, we started hearing grumblings about the audio archives. It was explained to me this way: Since the dawn of time, the House and Senate journals were the official record of what happened in the respective chambers. But those records could be amended. So if one member called another member “a lying motherfucker,” that got stricken from the official journal. But but not from our audio archives. This made lots of folks very uncomfortable and — ultimately — led to the legislature taking over. I always assumed some poor schmuck got stuck with editing those monster audio files.

UPDATE: I failed to mention the important role Phil Atkinson and Charlie Peters (and the people that worked with them) played in this (and other) digital project. I’d ask, “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could…” and in a few days (or hours!) they found a way to do it.

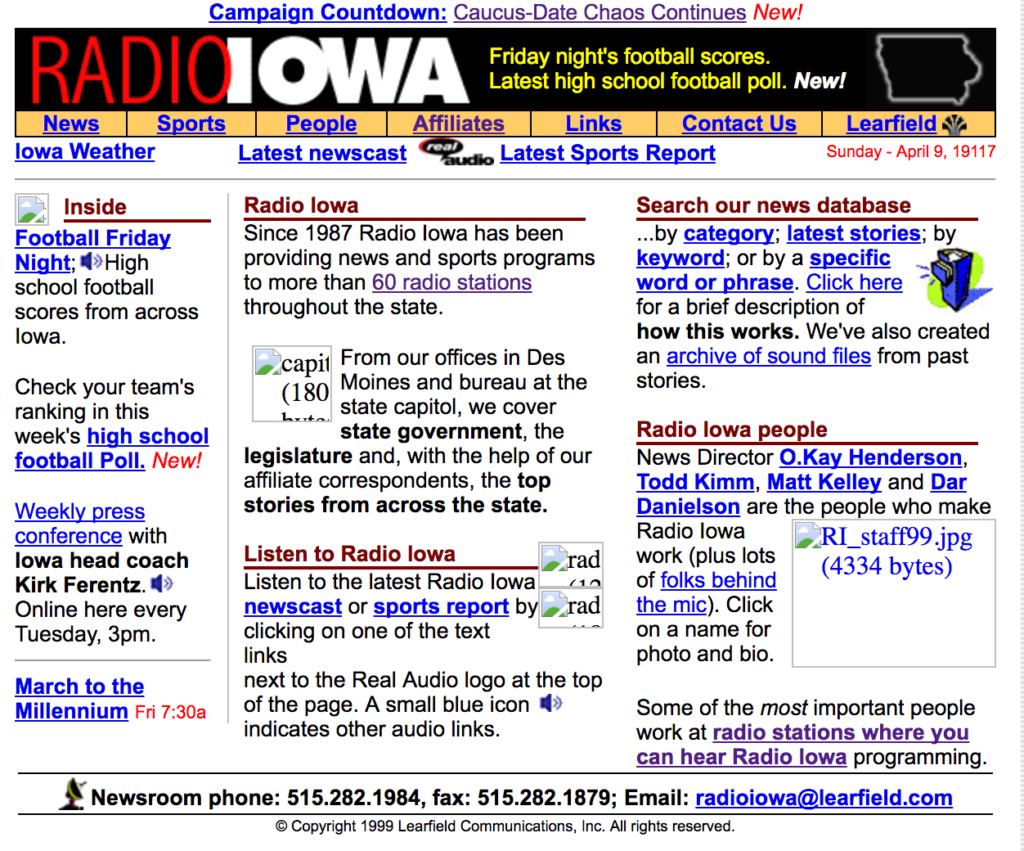

ANOTHER UPDATE: This was our first web page for this project. Really ugly, and really long.

This has such a Pony Express feel to me, here in 2017. The idea of a monthly, printed newsletter seems… quaint. But I recall almost every company and association doing a monthly (sometimes quarterly) newsletter. Somebody spent hours writing these things, often with multiple managers “signing off” before they went out.

This has such a Pony Express feel to me, here in 2017. The idea of a monthly, printed newsletter seems… quaint. But I recall almost every company and association doing a monthly (sometimes quarterly) newsletter. Somebody spent hours writing these things, often with multiple managers “signing off” before they went out.

That’s the question posed in a

That’s the question posed in a