“News items are bubbles popping on the surface of a deeper world.” I’m one week away from one full year without TV/Cable news. It stopped being an experiment a while back. It has been satisfying in ways I can’t really explain. This article takes a shot at it:

The daily repetition of news about things we can’t act upon makes us passive. […] Out of the approximately 10,000 news stories you have read in the last 12 months, name one that – because you consumed it – allowed you to make a better decision about a serious matter affecting your life, your career or your business.

News is to the mind what sugar is to the body. News is easy to digest. The media feeds us small bites of trivial matter, tidbits that don’t really concern our lives and don’t require thinking. That’s why we experience almost no saturation. Unlike reading books and long magazine articles (which require thinking), we can swallow limitless quantities of news flashes, which are bright-coloured candies for the mind.

Most news consumers – even if they used to be avid book readers – have lost the ability to absorb lengthy articles or books. After four, five pages they get tired, their concentration vanishes, they become restless. It’s not because they got older or their schedules became more onerous. It’s because the physical structure of their brains has changed.

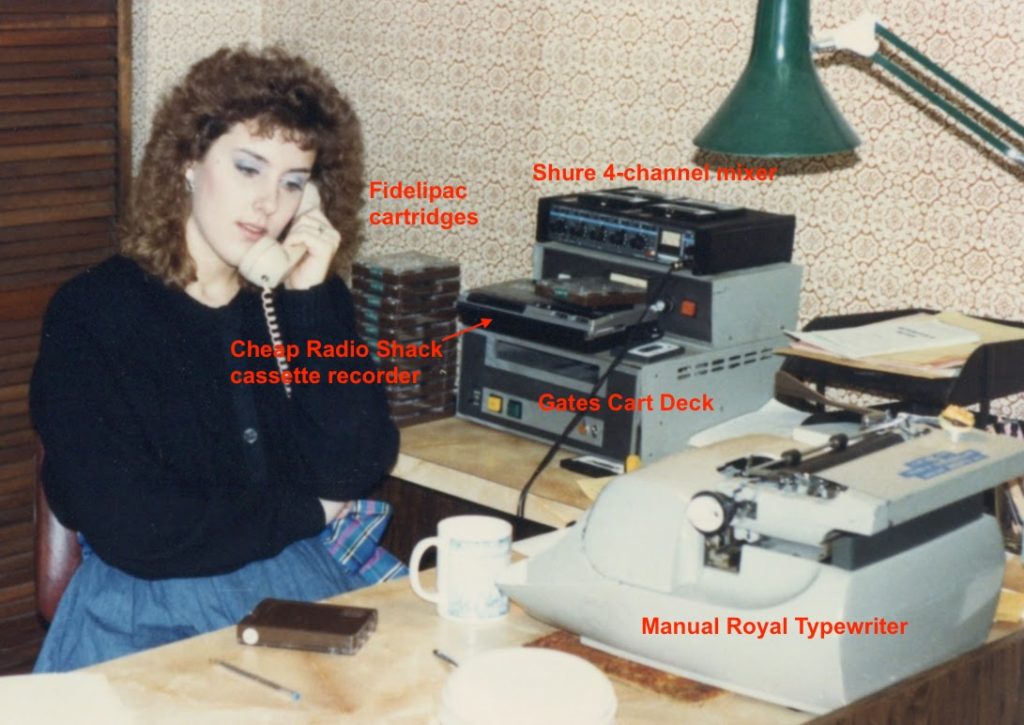

Our radio station didn’t have a national news network (until 1974) so we relied on the Associated Press newswire for just about everything throughout the day. During a live “board shift” we would dash to the AP teletype (in the transmitter room) and “rip the wire” which involved tearing a long strip of printed wire copy into piles of news, weather, sports, entertainment news, etc. If the paper jammed or the ribbon broke, we missed whatever was fed. If something the AP considered urgent was fed, an alarm bell on the teletype sounded.

Our radio station didn’t have a national news network (until 1974) so we relied on the Associated Press newswire for just about everything throughout the day. During a live “board shift” we would dash to the AP teletype (in the transmitter room) and “rip the wire” which involved tearing a long strip of printed wire copy into piles of news, weather, sports, entertainment news, etc. If the paper jammed or the ribbon broke, we missed whatever was fed. If something the AP considered urgent was fed, an alarm bell on the teletype sounded.