Yesterday I subscribed to the digital edition of the New York Times. I think this is the first time I have paid for news online. I’ll pay $3.75 per week, less than the cost of a double-espresso at The Coffee Zone.

Category Archives: Internet

The Internet Is Using Us

Media Theorist Douglas Rushkoff explains how the need for rapid corporate and economic growth has always been great for aristocracy, but bad for everyone else. My notes (PDF) from Mr. Rushkoff’s book, Throwing Rocks At the Google Bus. Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus – Douglas Rushkoff

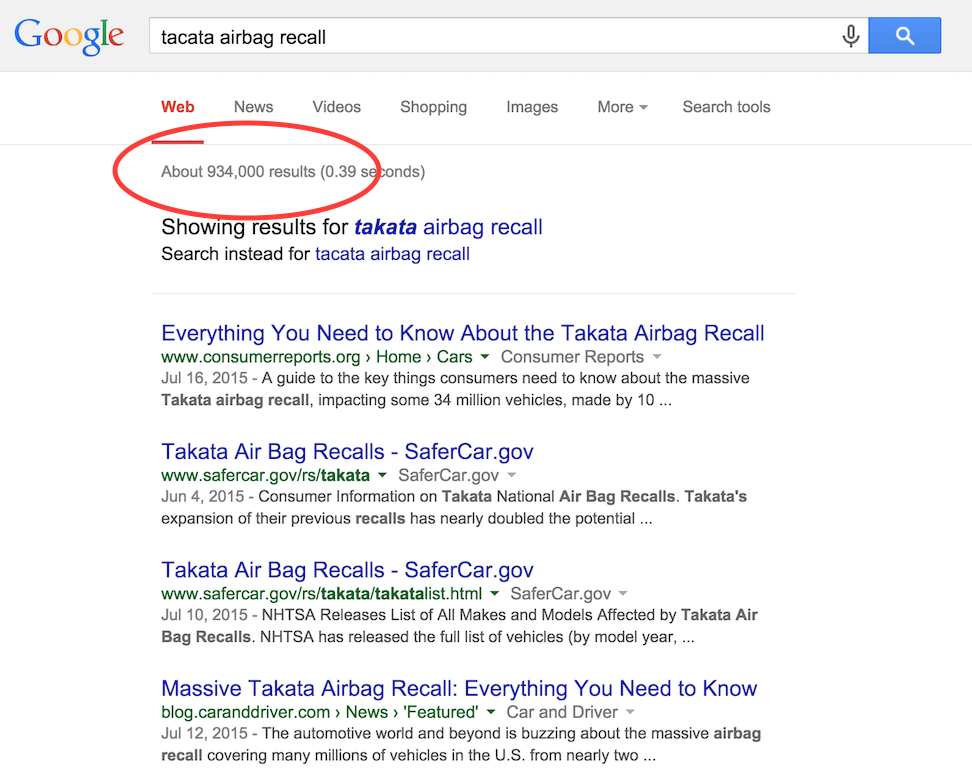

Recall? What recall?

While getting my car serviced (at the MINI dealership in St. Louis) earlier this week I mentioned the Takata airbag recall and the young man at the part window got puzzled look on his face.

“You’ve heard about the exploding airbag canisters and the big recall, right?

Nope, he insisted. He hadn’t heard about any airbag recall. About that time another young man came up to the next part window so I asked him. Same response. Had no idea what I was referring to.

I’m certain they weren’t fucking with me. Somehow they had missed seeing/hearing/reading _anything_ about this long-running story. I find that amazing.

Unless I’m missing something here, this means these two men could not have watched a network or cable newscast, read a newspaper, or spent 2 minutes on an online news site for the past 6 months (longer?).

How is that possible? And what else is going on in the world about which these young men are oblivious? I assume they’re on Facebook and would have seem some reference to this story there. No?

The end of capitalism has begun

The provocative headline of this article (by Paul Mason in The Guardian) is enough to make some dismiss it out of hand. I hope you’ll give these excerpts a quick scan and, if you see something interesting, click through to the article.

- Information is a machine for grinding the price of things lower and slashing the work time needed to support life on the planet. As a result, large parts of the business class have become neo-luddites. Faced with the possibility of creating gene-sequencing labs, they instead start coffee shops, nail bars and contract cleaning firms: the banking system, the planning system and late neoliberal culture reward above all the creator of low-value, long-hours jobs.

- We’re surrounded not just by intelligent machines but by a new layer of reality centred on information. Consider an airliner: a computer flies it; it has been designed, stress-tested and “virtually manufactured” millions of times; it is firing back real-time information to its manufacturers. On board are people squinting at screens connected, in some lucky countries, to the internet. Seen from the ground it is the same white metal bird as in the James Bond era. But it is now both an intelligent machine and a node on a network. It has an information content and is adding “information value” as well as physical value to the world. On a packed business flight, when everyone’s peering at Excel or Powerpoint, the passenger cabin is best understood as an information factory.

- The knowledge content of products is becoming more valuable than the physical things that are used to produce them.

- Today the whole of society is a factory. We all participate in the creation and recreation of the brands, norms and institutions that surround us. At the same time the communication grids vital for everyday work and profit are buzzing with shared knowledge and discontent. Today it is the network – like the workshop 200 years ago – that they “cannot silence or disperse.”

- By creating millions of networked people, financially exploited but with the whole of human intelligence one thumb-swipe away, info-capitalism has created a new agent of change in history: the educated and connected human being.

- The power of imagination will become critical. In an information society, no thought, debate or dream is wasted – whether conceived in a tent camp, prison cell or the table football space of a startup company.

- The democracy of riot squads, corrupt politicians, magnate-controlled newspapers and the surveillance state looks as phoney and fragile as East Germany did 30 years ago.

We are data: the future of machine intelligence (2015)

“Artificial Intuition happens when a computer and its software look at data and analyze it using computation that mimics human intuition at the deepest levels: language, hierarchical thinking — even spiritual and religious thinking. The machines doing the thinking are deliberately designed to replicate human neural networks, and connected together form even larger artificial neural networks.”

This is from an article by Douglas Coupland. Maybe one of the more frightening things I’ve read about data collection. Let’s start with a few of one-liners:

“Amazon can tell if you’re straight or gay within seven purchases.”

“Doug’s Law: An app is only successful if it puts a lot of people out of work.”

“The amount of internet freedom we have right now is the most we’re ever going to get.”

He starts his piece with a description of an imaginary app called Wonkr. I had to read this a few times to decide if he was serious or not.

“You put Wonkr on your phone and it asks you a quick set of questions about your beliefs. Then, the moment there are more than a few people around you (who also have Wonkr), it tells you about the people you’re sharing the room with. You’ll be in a crowded restaurant in Nashville and you can tell that 73 per cent of the room is Republican. Go into the kitchen and you’ll see that it’s 84 per cent Democrat. You’ll be in an elevator in Manhattan and the higher you go, the percentage of Democrats shrinks. Go to Germany — or France or anywhere, really — and Wonkr adapts to local politics. The thing to remember is: Wonkr only activates in crowds. If you’re at home alone, with the apps switched off, nobody can tell anything about you.”

“Wonkr’s job is to tell you the political temperature of a busy space. “Am I among friends or enemies?” But then you can easily change the radius of testability. Instead of just the room you’re standing in, make it of the block or the whole city — or your country. Wonkr is a de facto polling app. Pollsters are suddenly out of a job: Wonkr tells you — with astonishing accuracy — who believes what, and where they do it.”

“Wonkr is a free app but why not help it by paying say, 99 cents, to allow it to link you with people who think just like you. Remember, to sign on to Wonkr you have to take a relatively deep quiz. Maybe 155 questions, like the astonishingly successful eHarmony.com.”

If you’re busy, put this aside until you have 10 minutes. It’s packed tighter than cocaine mule’s carry-on.

Dick, from the Internet

The AI we confront will be us

From an article by Tim O’Reilly

“When news of import spreads around the world in moments, is this not the awareness in some kind of global brain? When an idea takes hold in millions of individual minds, and is reinforced by repetition across our silicon networks, is it not a persistent thought?”

It’s a rare day I don’t “ask Google” a question. Usually several. Increasingly, Google provides a useful answer. As this bit of magic becomes commonplace, the line between Me and the Net becomes thinner and thinner and will soon disappear. (Already, perhaps?) My mind (whatever that is) feels like it’s escaping the cramped confines of my head and it feels wonderful.

“AI that we will confront is not going to be a mind in an individual machine. It will not be something we look at as other. It may well be us.”

As our Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal ancestors slowly became what we are today?

The SMAYS Award

The company I worked for holds an annual meeting of their sales reps that includes an awards ceremony. The awards are called the Clydes in honor of the company founder (Clyde Lear). Sort of like the Oscars but, well, the Clydes. One of the categories — Digital Sales — is named after me. I was pretty annoying in the late 90’s and early 00’s on the subject of the Internet. Lots of eye rolling back then, big part of the company’s revenue today. This is, I’m convinced, a short-lived vanity. It already seems odd to refer to something as digital when everything is, and has been, digital for a long time.

Derry Brownfield Show: World Wide Web

The Internet has become so much a part of our lives it feels strange to say/write the word. Hard to remember a time when it was new and strange. The interview segment below is from 1996 and is a tiny time capsule from those early days of the “world wide web.”

On September 11, 1996, Allen Hammock was the guest on Derry Brownfield’s radio show to talk about the Internet and the “World Wide Web.” Allen and his partner, Dan Arnall, had recently joined Learfield Communications to “explore opportunities” on this new thing called the Internet. Allen and Dan were recent graduates of the University of Missouri in Columbia, MO. They created the first websites for our company and worked with our IT department to stream audio for our various radio networks and programs, including The Derry Brownfield Show. This 13 minute segment (edited from an hour-long show) touches on: Personal Communication, Privacy and Security, computer viruses, and getting “on” and “off” the Internet.

On November 22, 1996, Derry did a follow-up show featuring Solveig Bernstein, talking about privacy (and other topics) on the Internet (still newish at the time). Ms. Bernstein was the Assistant Director of Telecommunications and Technology Studies for the Cato Institute.

MCI Internet Service

November 21, 1994: $49.95 for software; $19.95/mo (7 hours free; $3.00 per hour after that). 9600 baud/14400. And I was thrilled to get it.