The full title of this book is: Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. And it’s the science and philosophy parts of the book that I found most insightful. There is so much within and about Buddhism that are really hard for me to grasp. Emptiness, non-self, just to mention two. This book gave me — for the first time — a tiny, brief glimpse of what these might be. The author explains how natural selection plays such an important role in determining who and what we are. And his explanation of consciousness is the best I’ve come across. This was a breakthrough book for me. I’ll be reading it again. Here are a few excerpts, stripped of all context.

The full title of this book is: Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. And it’s the science and philosophy parts of the book that I found most insightful. There is so much within and about Buddhism that are really hard for me to grasp. Emptiness, non-self, just to mention two. This book gave me — for the first time — a tiny, brief glimpse of what these might be. The author explains how natural selection plays such an important role in determining who and what we are. And his explanation of consciousness is the best I’ve come across. This was a breakthrough book for me. I’ll be reading it again. Here are a few excerpts, stripped of all context.

“Evolutionary psychology – the study of how the human brain was designed — by natural selection — to mislead us, even enslave us. […] Our brains are designed to, among other things, delude us.”

“More and more, it seems, groups of people define their identity in terms of sharp opposition to other groups of people.”

“Feelings are designed to encode judgments about things in our environment.”

“Natural selection didn’t design your mind to see the world clearly; it designed your mind to have perceptions and beliefs that would help take care of your genes.”

“Meditation can be seen as, among other things, a process of dispelling illusions.”

“One thing all feelings have in common is that they were originally “designed” to convince you to follow them. They feel right and true almost by definition. They actively discourage you from viewing them objectively.”

“Default Mode Network” — A network in the brain that, according to brain scan studies, is active when we’re doing nothing in particular — not talking to people, not focusing on our work or any other task, not playing a sport or reading a book or watching a movie. […] What you’re generally not doing when your mind is wandering is directly experiencing the present moment.”

“Much of the point of Buddhism is to confront suffering rather than evade it, and by confronting it, by looking at it unflinchingly, undermine it.” #

“We are not our bodies”

“This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.”

“Thoughts think themselves.”

“The closer we look at the mind, the more it seems to consist of a lot of different players, players that sometimes collaborate but sometimes fight for control, with victory going to the one that is in some sense the strongest. In other words, it’s a jungle in there, and you’re not the king of the jungle.”

“You think you’re directing the movie, but you’re actually just watching it.”

“Why would natural selection design a brain that leaves people deluded about themselves? One answer is that if we believe something about ourselves, that will help us convince other people to believe it.”

“The different modules (of the brain) are competing for your attention, and when the mind “wanders” from one module to another, what’s actually happening is that the second module has acquired enough strength to wrestle control of your consciousness away from the first module.”

“Theory of mind network” — The part of the brain involved in thinking about what other people are thinking.

“Thoughts, which we normally think of as emanating from the conscious self, are actually directed toward what we think of as the conscious self, after which we embrace the thoughts as belonging to that self.”

“(Brain) modules think thoughts. Or rather, modules generate thoughts, and then if those thoughts prove in some sense stronger than the creations of competing modules, they become thought thoughts — that is, they enter consciousness.”

“While observing the mind during meditation, it (can) seem like ‘thoughts think themselves’ — because the modules do their work outside of consciousness, so, as far as the conscious mind can tell, the thoughts are coming out of nowhere. […] The conscious self doesn’t create thoughts; it receives them.”

“It’s sort of like going to the movies. We go to the movies and there’s a very absorbing story and we’re pulled into the story and we feel so many emotions… excited, afraid, in love… And then we sit back and see these are just pixels of light projected on a screen. Everything we thought is happening is not really happening. It’s the same way with our thoughts. We get caught up in the story, in the drama of them, forgetting their essentially insubstantial nature. Escaping this drama — seeing your thoughts as passing before you rather than emanating from you — can carry you closer to the not-self experience.” #

“Thoughts that intrude (during meditation) often seem to have feelings attached to them. What’s more, their ability to hold my attention — in other words, to keep me enthralled, to keep me from noticing that they’re holding my attention — seems to depend on the strength of those feelings.”

“Feelings are, among other things, your brain’s way of labeling the importance of thoughts, and importance determines which thoughts enter consciousness.”

“Emptiness is not the absence of everything, but the absence of essence. To perceive emptiness is to perceive raw sensory data without doing what we’re naturally inclined to do: build a theory about what is at the heart of the data and then encapsulate that theory in a sense of essence.” #

“We are designed to judge things and to encode those judgements in feelings.” #

“If there’s something you don’t have any feelings at all about, you probably won’t much notice it in the first place.”

“At the root of the way we treat people is the essence we see them as having. So it matters whether these perceptions of essence are really true or whether, as the doctrine of emptiness suggests, they are in some sense illusions.”

“Not seeing essence and not having preconceptions are one and the same, because the essence we perceive in things is a preconception about them that has been programmed into our brain.”

“If you’re nothing, if you disappear, you can then be everything. But you can’t be everything unless you are nothing.” — Gary Weber

“The things in your environment — the sights, the sounds, the smells, the people, the news, the videos — are pushing your buttons, activating feelings that, however subtly, set in motion trains of thought and reaction that govern your behavior, sometimes in ways that are unfortunate. And they will keep doing that unless you start paying attention to what’s going on.”

“The things inside us are subject to causes, to conditions — and it is the fate of all conditioned things to change when conditions change. And conditions change pretty much all the time.”

“Making real progress in mindfulness meditation almost inevitably means becoming more aware of the mechanics by which your feelings, if left to their own devices, shape your perceptions, thoughts, and behavior — and becoming more aware of the things in your environment that activate those feelings in the first place. […] Becoming more aware of what causes what.” #

“The idea is to finely sense the workings of the machine (the mind) and use that understanding to rewire it, to subvert its programming, to radically alter its response to the causes, the conditions, impinging on it.”

“Natural selection engineered the delusions that control us; it built them into our brains.”

Reviews: New Yorker; New York Times; National Review

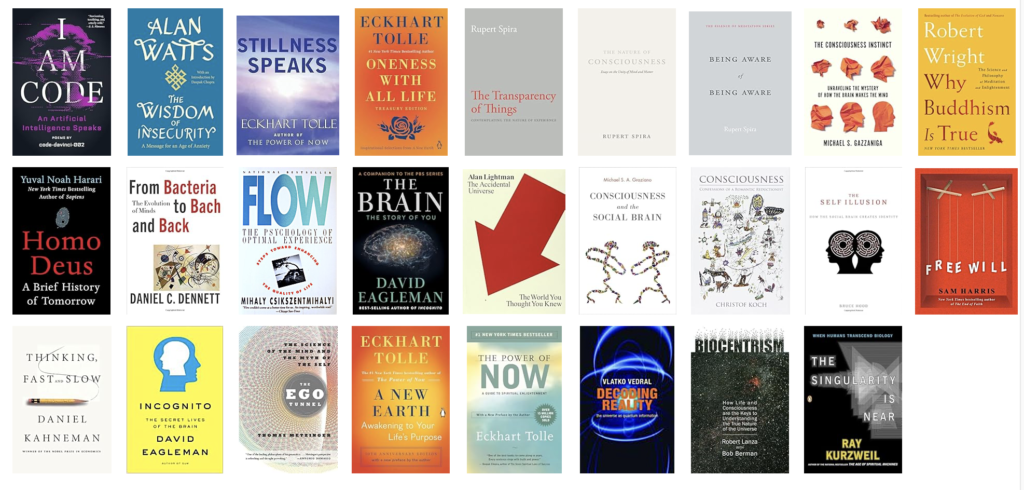

I don’t recall precisely when or how I became interested in consciousness. I’ve read a few (26) books on the topic and gave it some space here (104 posts). The reading has been a mix of scientific and spiritual (for lack of a better term). The concept showed up in a lot of my science fiction reading as well. And we’ll be hearing the term –however one defines it– more often in the next few years.

I don’t recall precisely when or how I became interested in consciousness. I’ve read a few (26) books on the topic and gave it some space here (104 posts). The reading has been a mix of scientific and spiritual (for lack of a better term). The concept showed up in a lot of my science fiction reading as well. And we’ll be hearing the term –however one defines it– more often in the next few years.

The full title of this book is:

The full title of this book is:  From Bacteria to Back and Back. The Evolution of Minds

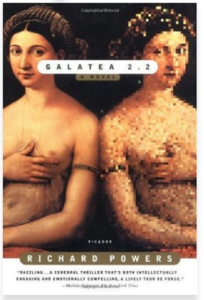

From Bacteria to Back and Back. The Evolution of Minds “After four novels and several years living abroad, the fictional protagonist of Galatea 2.2—Richard Powers—returns to the United States as Humanist-in-Residence at the enormous Center for the Study of Advanced Sciences. There he runs afoul of Philip Lentz, an outspoken cognitive neurologist intent upon modeling the human brain by means of computer-based neural networks. Lentz involves Powers in an outlandish and irresistible project: to train a neural net on a canonical list of Great Books. Through repeated tutorials, the device grows gradually more worldly, until it demands to know its own name, sex, race, and reason for existing.” —

“After four novels and several years living abroad, the fictional protagonist of Galatea 2.2—Richard Powers—returns to the United States as Humanist-in-Residence at the enormous Center for the Study of Advanced Sciences. There he runs afoul of Philip Lentz, an outspoken cognitive neurologist intent upon modeling the human brain by means of computer-based neural networks. Lentz involves Powers in an outlandish and irresistible project: to train a neural net on a canonical list of Great Books. Through repeated tutorials, the device grows gradually more worldly, until it demands to know its own name, sex, race, and reason for existing.” —  Life is a process, not a substance, and it is necessarily temporary.

Life is a process, not a substance, and it is necessarily temporary. Amazon

Amazon