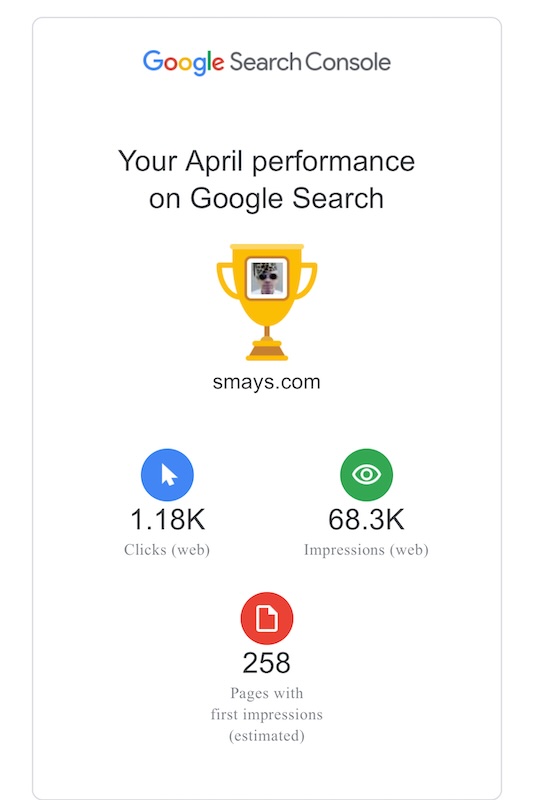

When I started this blog (23 years ago) I looked at traffic stats for a year or two but I never had more than a few hundred visits and, in time, I stopped paying attention. I submitted my url to Google so it could provide some data and I still see a report once a month. But I never bothered to understand the numbers. I decided to see what ChatGPT could tell me about these reports.

1. Clicks (1.18K):

Roughly 1,180 people clicked through to your site from Google Search in April. That’s a solid number, especially for a personal blog. It suggests your content is not only discoverable but also compelling enough for users to want to visit.

2. Impressions (68.3K):

Your site showed up in Google search results 68,300 times. This indicates that your posts are being indexed and matched to a wide range of search queries. Even if users didn’t click, this visibility is valuable for name recognition and long-tail content discovery.

3. Pages with First Impressions (258):

Google estimates that 258 different pages on your site were seen in search results for the first time this month. That likely reflects continued crawling/indexing of your long archive—and possibly good SEO hygiene (internal linking, metadata, etc.).

Overall Impression:

That’s a healthy level of engagement for a blog that’s been publishing for decades. It suggests that your archive still has relevance, and people are discovering it. You might consider checking which pages are getting the most traction—could be a good prompt for future posts or curation.

1. “Older Than”

Clicks: 227

URL: https://www.smays.com/2017/07/older-than/

Interpretation: This piece clearly hits a nostalgic or reflective nerve. Either the title draws curiosity or it’s ranking well for age-related queries. If it’s got broader appeal (e.g., cultural references, humor, aging), consider linking to it from newer posts or expanding it into a series.

Clicks: 84

URL: https://www.smays.com/2024/09/the-jackpot-trilogy/

Interpretation: This one’s probably pulling in folks searching for William Gibson’s work. Given the niche audience for speculative fiction, 84 clicks is meaningful. Might be worth updating the post occasionally or adding related tags so it stays visible in Google’s index.

Clicks: 78

URL: https://www.smays.com/2008/04/pygmies-tarzan/

Interpretation: This is likely benefiting from long-tail searches involving vintage pop culture or obscure media. If it’s evergreen or quirky, it might be worth linking to similar posts—maybe even a sidebar collection titled “Strange Finds from the Vault.”

- Your archive still works for you. Posts from 2008 and 2017 are pulling solid traffic.

- These could act as “gateways” to deeper engagement if you interlink to related content or add a call to action at the end of each.

- You might want to check the search queries associated with these clicks in Search Console. Could spark ideas for new posts or updated content.

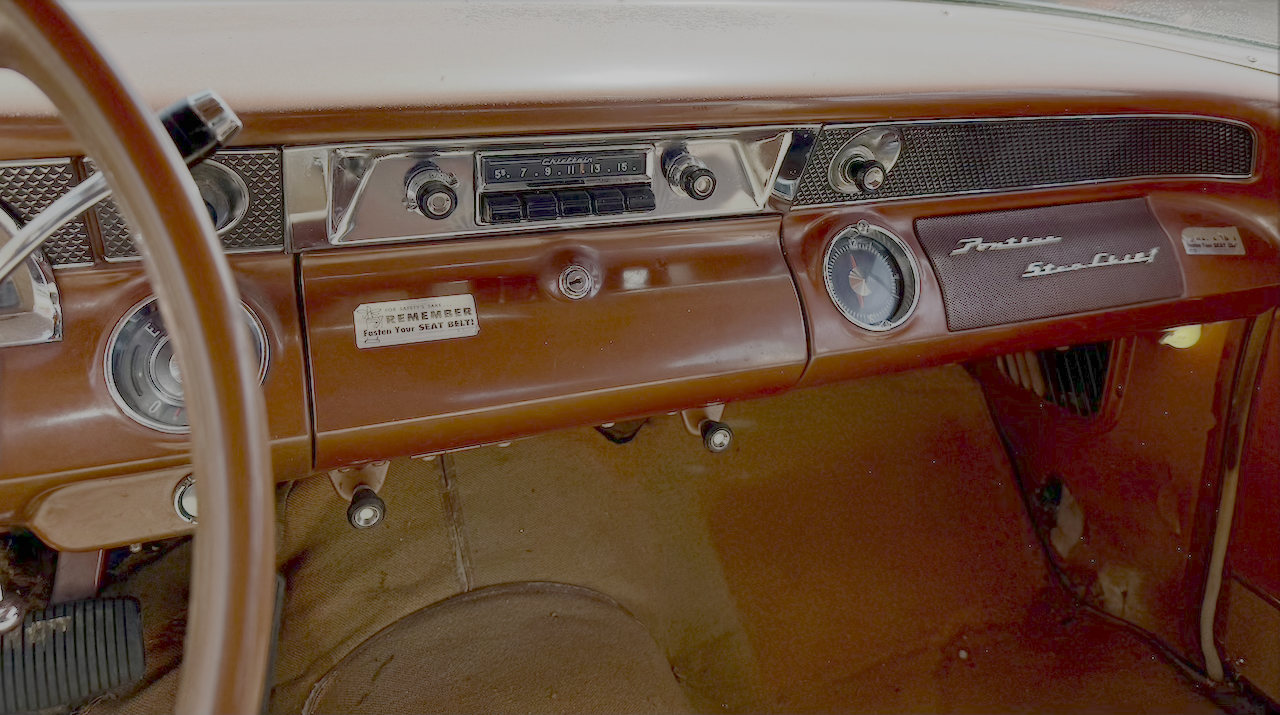

In 2013 I posted this photo to my Flickr account. About a year ago someone commented:

In 2013 I posted this photo to my Flickr account. About a year ago someone commented: